It's Not Difficult to End Our 'Driving While Black' Problem

Three easy solutions come to mind immediately.

Most people don’t say the N-word anymore, but the lingering idea behind it endangers us all.

With all eyes on the trial of Derek Chauvin, you’d think police everywhere would be on high alert regarding their behavior. That they’d want to distance themselves from incidents that tarnish the reputation of all police.

But during the height of Chauvin’s trial, the news was filled with two incidents of “driving while Black” that made cops look bad all over again.

The worst of these ended with the death of Daunte Wright, a 20-year-old Black man killed by accident on April 11 for allegedly avoiding arrest. His death triggered violent protests and clashes with police in Brooklyn Center, MN, a suburb of Minneapolis where tensions have been high for weeks in anticipation of potential violence following the Chauvin trial.

The other incident took place last December, but the video did not begin its viral spiral till the weekend of April 9. That’s how we witnessed the inhumane treatment of Lt. Caron Nazario, who is Black and Latino, when he was pulled over by two police in Windsor, Virginia.

George Floyd was not killed for ‘driving while Black.’

His death was precipitated by a call to police regarding a fake $20 dollar bill. But Daunte Wright did lose his life during a traffic stop, and Lt. Nazario might have lost his had he tried to obey the conflicting commands issued by the two police officers who pulled him over, one of whom has since been fired.

However, all three cases have a single unifying cause, which is made clear in a telling moment during Lincoln, Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film about the efforts of the 16th U.S. president to pass an amendment abolishing slavery.

Spielberg’s Lincoln

Early in the movie, the president asks a white couple from Missouri if they’d support the elimination of slavery if it would end the Civil War. They say yes.

But when he asks if they’d still support the amendment if it were possible to end the war without abolishing slavery, they say no.

“Why not?” Lincoln asks.

“Well, niggers,” they say.

In case you’ve been cryogenically frozen since the Big Bang, nigger is an offensive, insulting word for a Black person and, more widely, any member of a dark-skinned race. The grotesque honesty of the Missouri couple’s use of that word — and its presence in American history long before 1864, when it was added to the dictionary—is at the root of why “driving while Black” remains dangerous.

Driving while Black is not about something people of color do behind the wheel.

It’s about the likelihood of being stopped by police if you’re Black — and how your treatment during a traffic stop can end with your death.

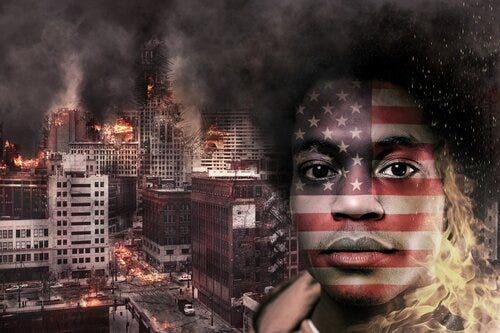

Even though many whites no longer say the word publicly, the thought behind the word nigger has never disappeared. And whether it’s spoken or not, the persistent idea of nigger — of base, subhuman inferiority — makes it possible to treat people of color with contempt. That concept fueled the racial hatred that led to the murder of George Floyd and the civil unrest that turned peaceful protests into an explosion of violence in several major cities last year.

The unrest threatened the safety of individuals and businesses wherever it occurred. Fires, looting, and assault replaced the civil order we all depend on for our families and our livelihoods.

Even Chicago’s Magnificent Mile was not spared. When rioting broke out in Atlanta after a Black motorist was shot in the back, a stray bullet killed an eight-year-old girl. North of the city, suburban residents queued up to buy guns and register for concealed-carry permits.

Precautions

As witnesses during the Chauvin trial revisited Floyd’s death, it was unsettling to see the level of precautionary measures needed to protect the city should Chauvin not be convicted of murder.

Two thousand National Guard troops have been placed on call to support 1,000 local police officers. Barbed wire has gone up. Business storefronts boarded. Streets barricaded. People have appeared on television openly speaking about the potential for extremely violent protests when the trial ends.

The phrase no justice, no peace means one thing to those who regard violence as a justifiable response to systemic unfairness. Others view it as a form of extortion. Give us the outcome we want, or we will tear the place to pieces.

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to explain to the latter group why politically and socially disenfranchised people regard violence as the only way to make their voices heard by a system in which they feel routinely victimized.

The Heart of the Matter

In last year’s fraught and polarized political environment, Americans rallied behind two extremes. Calls to defund the police were met with equally shrill cries for law and order, a catchphrase seen as a green light for police brutality since the Nixon/Agnew years.

It makes sense that discussions about racial tension in our cities should focus on police, since their behavior has triggered much of it.

But shouldn’t we also know how our public safety officers feel about people of color? To what extent are they subject to internalized and unrecognized beliefs about people they may regard as niggers, whether they say this word or not?

The long list of cases in which Black people have died at the hands of white police officers is connected by the same concept that underlies the N-word. The deep-seated belief that some lives are unworthy of equal treatment endangers us all.

Lt. Nazario

Investigations may eventually reveal how the officer who killed Daunte Wright mistook her gun for a taser on April 11.

But although an investigation has been launched into the separate driving-while-Black incident involving Lt. Caron Nazario in Virginia, the video released on April 9 (and shown below) provides compelling evidence of why rigorous psychological testing of our police is imperative. (Viewer discretion advised)

A graduate of the ROTC program at Virginia State University, Lt. Nazario was on his way home from work last December 5, driving a new Chevy Tahoe with a temporary tag taped to the rear window.

Two Windsor, Virginia, police officers (Daniel Crocker and Joe Gutierrez) pulled him over, held him at gunpoint, pepper-sprayed him four times, yanked him from the car, assaulted him, threw him to the ground, and placed him in handcuffs. One of them even said, “You fixin’ to ride the lightning,” a threat based on slang that refers to death in the electric chair.

All without Cause

Except of course, that Lt. Nazario was driving while Black. Had he been white, the police would have asked him if he had a tag. He would have told them it was taped to the window because he’d just purchased the car and the permanent ones had not yet arrived. They would have looked at the window, seen the temporary tag, and said, “Okay, sir. Thank you for your service to our country. Have a nice day.”

Blacks are 95% more likely than whites to be pulled over by police and 115% more likely to be searched.

If you’re not Black, you may not know that you try to find a brightly lit place when the police pull you over. Far too many Black men have been beaten by the side of a dark road by white cops who later claim you were “obstructing” or “resisting arrest.” Given what happened to Nazario under the LED canopy of a BP gas station, it’s not hard to understand why he was reluctant to pull over in the dark.

Forget Nazario’s college degree

Also forget the uniform of an army officer. None of it mattered to those two police officers. It also did not matter that Lt. Nazario spoke in a normal, non-threatening, non-hostile voice when he asked why he was being stopped.

All the police saw was the color of his skin. Although neither of them used the word — what they saw was a nigger. And that is how they treated him. Like something less than human.

Projection of the Shadow

To see a “nigger” — whether you say that word or not — is to see something you fear. As James Baldwin pointed out in somewhat Jungian terms, you are seeing your own shadow, the unacknowledged darkness of your own psyche. I’m not a nigger, Baldwin said. The nigger is something inside of you, which you are trying to put on me. You are doing this because for some reason, you need the nigger.

This tendency is not new, and it’s not unique to America.

During the 14th-century plague in Europe, the pogroms in 19th-century Russia, and Kristallnacht in 1938 Germany, folks in those places routinely projected their collective shadow onto Jewish scapegoats.

Unfortunately, projection is an unconscious phenomenon. If you watch the body-cam video of Lt. Nazario’s traffic stop, you will hear the fear beneath the police officer’s barked orders. He’s yelling because he is terrified of what he imagines Nazario to be. He sounds angry, but psychologists will tell you anger is a secondary emotion that covers the primary emotion of fear.

Three Ways to End Racial Profiling by Police

Lt. Nazario managed to walk away from what happened that night. He has since filed a lawsuit alleging that his First and Fourth Amendment rights under the U.S. Constitution were violated. Officer Gutierrez has been terminated.

But given that this video went viral during Chauvin’s trial — the same weekend Daunte Wright was killed, one year after the killing of Breonna Taylor, and nearly a year after the murder of Ahmaud Arbery by police wannabes — we know, sadly, that this may not be the last time something like this goes viral.

If, as a nation, we really want to end these incidents, here are three easy ways to do so:

First:

Follow longstanding guidelines listed by Campaign Zero, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Southern Poverty Law Center to identify and track instances of racial profiling.

Things like ending pretext stops, setting federal standards for all traffic stops, increased community oversight, greater minority representation, enforcing existing Justice Department standards on racial profiling, and establishing periodic scenario-based training on what profiling is and how to deescalate potentially difficult encounters.

A recent study of 20 million traffic stops over a 14-year period in North Carolina alone shows that Blacks are 95% more likely than whites to be pulled over by police and 115% more likely to be searched.

The last time I was pulled over near my home north of Atlanta, the white policeman said he did so because it was a beautiful Spring day, I was driving with the top down on my convertible, and he was stuck in a hot police cruiser. The encounter ended with laughter, but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t nervous.

According to national data compiled by Mapping Police Violence, Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police and 1.3 times more likely to be unarmed.

Second:

Emulate the millitary’s current stand-down training to weed out extremists with white supremacist leanings and affiliation with groups associated with domestic terrorosim. Because police who threaten and kill Black motorists are just that — terrorists.

Third:

Require psychological testing as a condition of employment. Instruct police officers on how to become conscious of internal fears and the tendency to project them. Along with implicit-bias training, these tools could become game changers for our cities.

Recent history tells us that when “driving while Black” turns deadly, the consequences for our communities are destabilizing and destructive, threatening our businesses and our neighborhoods.

That’s why it’s in our interest to get behind reasonable measures to rid our police of internalized beliefs that make them ineffective and a danger to our communities. This is different from reallocating resources or demilitarizing police departments. Our police represent us on the streets. They should reflect who we are and what we believe.

Because fear is the enemy. Not Black people nor members of any ethnic minority. It’s fear we’re all afraid of. And no gun will ever protect us from it.

© 2021 Andrew Jazprose Hill