Stagger Lee and the 'Erasure' of Middle-Class African Americans

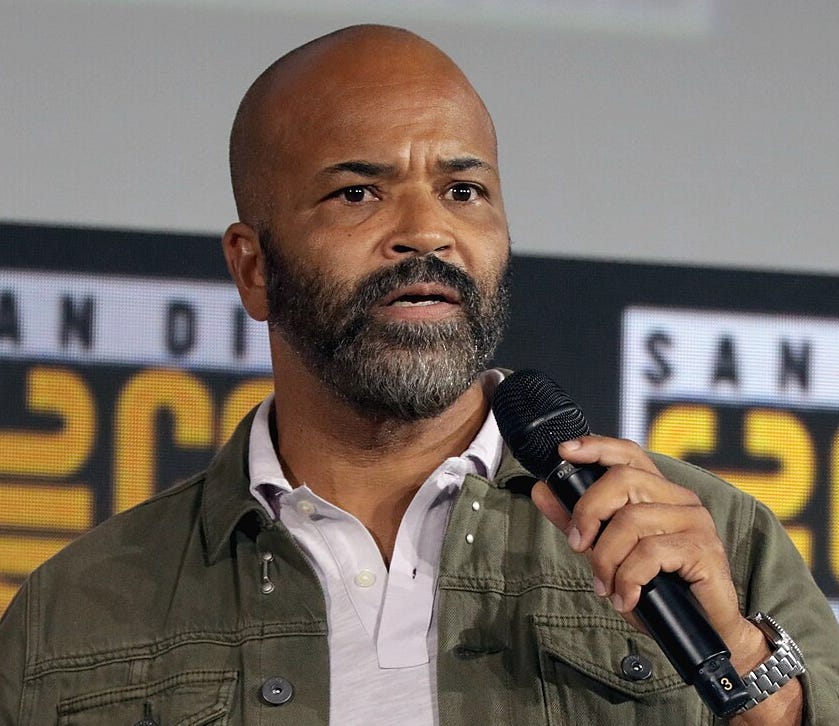

What better time than Black History Month to talk about Jeffrey Wright's hit movie 'American Fiction' and the very bad nigga at the center of the story.

Stagger Lee shot Billy.

He shot that poor boy so bad that the bullet went right through Billy and broke the bartender’s glass.

The year is 1958. I am 10 years old, leaning against the floor-standing woodgrain radio whose music has set my entire household in motion.

The man on the radio is Lloyd Price, and he is singing about a legendary figure, the seriously bad nigga known as Stagger Lee. We don’t know that this song is based on a real-life figure from the late 19th and early 20th-century, whose name was Lee Shelton — defined online as an American criminal.

And we don’t care.

For us, ‘Stagger Lee’ is a song. It is music. And it’s dance.

My mother, who has been dead 10 years as I write this, is still a honey-hued beauty in her thirties in 1958. When that song begins to play, she flies from the kitchen, turns up the volume, claps her hands — and begins to dance.

She grabs whichever of us kids is closest and does the jitterbug. My mother is a contest-winning dancer and has always loved to dance. We will learn years later that some of our ancestry on her side of the family may stem from members of a dance troupe that emigrated from France to Louisiana before Napoleon sold it to Thomas Jefferson in 1803.

But in 1958 there is no ancestry.com, 23andme, or Henry Louis Gates, Jr., to help us find our roots. There is only the music. There is only the dance.

And as that music fills the three-bedroom house my parents purchased on Atlanta’s Mozley Place in 1952, we do not care that the song we are dancing to is about a murder.

This is a happy time for us.

My father has a steady job on the railroad and owns a Buick. The purchase of a home has put my parents in the running. Made them candidates for membership in America’s Black Middle Class.

They cannot see the end of the road from here. The Civil Rights Bill is still six years away. But they suspect or at least hope their journey will lead our family out of the segregated working-class into a world their children will inhabit as doctors, lawyers, psychologists.

But for now, we are possessed by such exuberant joy while “Stagger Lee” is playing, the moment will lodge in my memory forever. I will still be able to sing it years later without having to check Google for the lyrics.

I was standing on the corner when I heard my bulldog bark. He was barking at the two men who were gambling in the dark.

We are a seriously Catholic family.

And this song runs counter to the values my parents live by. We know this song is not about us. We do not relate to it anymore than we relate to the N-word, which we also know has nothing to do with us.

Still, even now I keep hoping Billy will not be dead. That he will get up off that barroom floor. Grab the gun from Stagger Lee, fight back, or at least get the hell out of there. But just like the real Billy Lyons, he is still dead after all these years.

Meanwhile, Stagger Lee lives on —

as legends often do. Music has granted him immortality. He’s right up there with Bad-Bad Leroy Brown and good ole John Henry who died with a hammer in his hand, Lawd, Lawd, who died with a hammer in his hand.

Now in the 21st-century, Stagger Lee has ascended into the celestial heights of literature, where he reigns as successful author Stagg R. Leigh, the nom de plume and alter ego of Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison, central character of Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction, starring Jeffrey Wright.

The movie is based on Percival Everett’s novel Erasure, which I happily discovered before it became a hit movie.

Believe me, ‘Erasure’ is awesome

And I fell in love with it as soon as I found pieces of myself reflected in its pages. Not only do I fall into the category of African Americans who have been told they are “not Black enough” — whatever the f-u-c-k that means — but like the book’s main character I also enjoy classical music, art, and literature.

So when the movie came out and people began to tell me that Jeffrey Wright’s character reminded them of me, I was already there.

Moviegoers have been spared the task of reading Stagg R. Leigh’s book — his novel within Monk’s main story — which is a good thing. Leigh’s book is vile and off-putting, though there are moments that feel poetic. Reading through Stagg R. Leigh’s novel after engaging with Monk, was the equivalent of being dragged from the adagio of Schubert’s Quintet in C-Major into the soundtrack of Straight Outta Compton.

This is not to say that one is better than the other. Merely that they are jarringly dissimilar.

There’s a real disconnect

between the refined voice of Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison and Stagg R. Leigh’s. But sticking with Leigh’s short novel about a man with four baby mamas is worth the bumpy ride it takes you on. Stagg R. Leigh’s main character is called Van Go. And you can’t help noticing his similarity to Bigger Thomas, the bad nigga of Richard Wright’s Native Son.

In Erasure, the white liberal employers of Native Son have been replaced by wealthy African Americans. There’s a blind woman in each. And in both books, the daughter of this employer is victimized by the bad nigga employee.

The term bad nigga has at least two meanings. On one hand, he is a hero who dares to live on his own terms despite the restrictions of the white establishment. In this sense, Kunta Kinte is a bad nigga. So is prizefighter Jack Johnson. Superfly is a bad nigga. And that cat Shaft—he’s a bad mutha-shut-yo-mouth.

Stagger Lee, on the other hand represents the bad nigga as criminal. The historic figure is a big-time pimp and a murderer.

But Erasure is about much more than the Stagger Lee persona. It’s also more than a satire on the implicit racism of the publishing industry.

The very title of Everett’s novel tells us it carries far more heft than any movie can possibly achieve.

There are at least 7 kinds of ‘erasure‘ in this book—and counting

First, it’s about about the erasure of ordinary middle-class African Americans by the white establishment’s penchant to amplify negative Black stereotypes. The novel Push was published a few years before Everett wrote Erasure in 2001. His novel is clearly a reaction to stories like that.

Another issue is the erasure of memory when Monk’s mother is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. We’ve also seen this same device put to good use—copied?— in Britt Bennett’s 2022 novel The Vanishing Half in order to make the same point.

There’s the erasure of Monk’s professional status when his mother’s illness forces him to choose between his tenured professorship on the West Coast and a meager ad hoc position in Washington, DC.

The memory of Monk’s father is also altered—if not entirely erased— by the discovery of letters after his death. These epistles reveal the father’s secret life and previously unknown offspring, which were erased when he chose duty and obligation over love.

There is the shocking literal erasure of human life by a senseless murder.

There is Monk’s personal erasure when he assumes the identity of Stagg R. Leigh in order to write about a character he loathes in a novel he detests.

And finally, there is the erasure of Monk’s brother Bill, a gay man whose sexuality and distrust of his brother, severs their relationship. Just as Stagger Lee kills Billy in the song, it is Monk’s inability to communicate with his own gay brother that essentially slays this Billy too.

In other words, ‘Erasure’ is brilliant on many levels. It is also very funny.

Except for literary circles where it was regarded as both seminal and prescient, Erasure languished virtually unknown for over 20 years. Now, thanks to a movie that could not have been made or appreciated by a mass audience during the time of Precious, a film version of Sapphire’s Push, it is finally getting the exposure it deserves.

Stagger Lee lives on and will continue to live on. But thanks to his literary doppelgänger, American Fiction, and Erasure—we can see that bad nigga with a new lens, one with nuance and perspective.

Though, if I’m being honest, the “Stagger Lee” I first heard back in 1958 is still a really good song to dance to.

I, too, felt sad for Billy when I heard that song back then. Today, I think about all the “Billys” that are shot and those who never had the chance others have had. I feel sad for them, too.

Maybe Erasure/American Fiction will begin a new conversation about identity and self reflection.

Both American Fiction and Erasure have been on my TBR but your wonderful piece moved them to the top of the list.