In 'Othello' Jake Gyllenhaal Goes After Denzel Washington Like Project 2025 on DEI

Call it 'passing strange' or mere coincidence. But there couldn't be a more relevant time to bring Shakespeare's play about racism, jealousy, and revenge to the Great White Way.

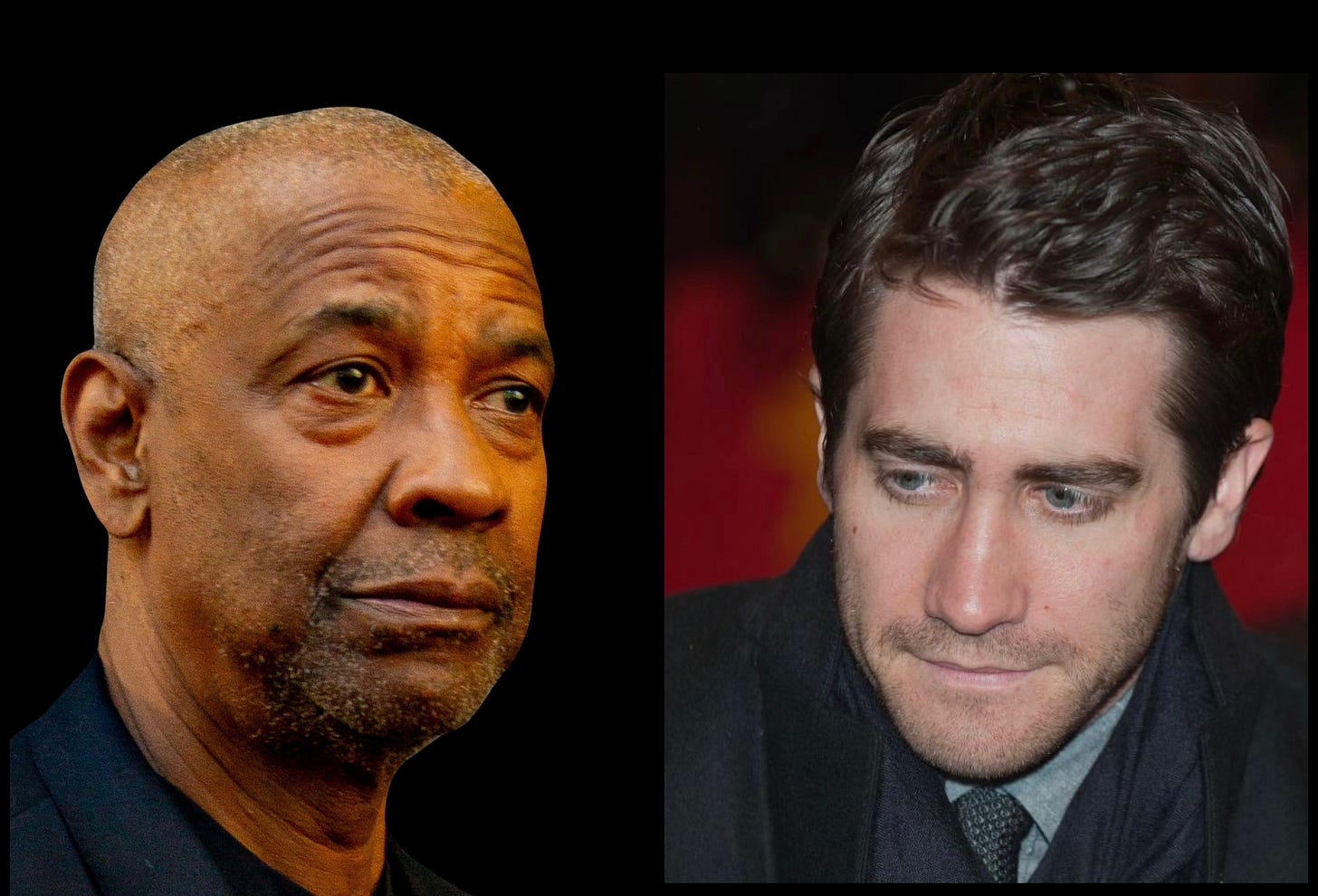

Before you rush out to see Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal in the Broadway revival of Othello, here’s the skinny on the play itself—and its significance at this particular moment in time.

When he was about 20, William Shakespeare came across an Italian novella about a nice girl who marries a Moor against her family’s wishes. The unnamed Moor is a distinguished general who truly loves his new wife but is deceived by a lieutenant into believing her unfaithful. In fact, the malicious lieutenant is angry because the general’s wife has ignored his advances.

Through skillful cunning, he gets his revenge when he and the deceived husband murder the wife, disguising her death as an accident. This heavy handed cautionary tale was meant to warn young women that a sad fate awaits them if they disobeyed the family’s wishes.

Twenty years later, Shakespeare thought about that old story again. By this time, he’d written 26 successful plays, including The Merchant of Venice, Romeo and Juliet, and Hamlet. Now at the top of his game and a wealthy man, he decided to write his own version. And that is how his Othello was born in 1604.

Shakespeare transforms the story from finger-wagging scare tactic into a poetic exploration of jealousy, racism, and revenge. Most of it written in iambic pentameter.

Othello is Aristotelian tragedy at its best. To experience this play — especially when it’s done well — is to be overcome with pity and fear. Unlike comedy, it delves deep into the human psyche, presses its finger on the painful sore spot, the core wound that has a counterpart of one kind or another within each of us.

Blackface vs Black skin

For the next two centuries, white actors darkened their skin slightly to make Othello seem Arab. When Ira Aldridge became the first African American to play the part at Covent Garden in 1833, some critics responded in starkly racist terms.

Since Shakespeare never says Othello is Black, calling him only a Moor, several critics were outraged. The poet Coleridge wrote “to imagine this beautiful Venetian girl (Desdemona) falling in love with a veritable negro” was “monstrous.” As a result the play was canceled after only two nights, even though audiences greeted Aldridge’s performance with enthusiasm.

Fast forward another 110 years to 1943 when the legendary Paul Robeson became the first African American to play Othello on the Great White Way. After Robeson, the drama was staged on Broadway three more times — each with African Americans in the title role.

In 1970 with Moses Gunn and more famously in 1982 with the illustrious James Earl Jones. And now, 43 years later, the EGOT known as Denzel Washington is putting his stamp on the role.

What the critics make of this production

—the price of the tickets, the casting, or Director Kenny Leon’s interpretation — is neither here nor there. On one level, it hardly even matters whether this new Othello is even great Shakespeare.

Because it’s already an event, grossing a record $2.8 million in a single week — the highest grossing play in history. As co-producer Ken Davenport explained last September, he backed the show because it was bound to be exactly that — an event. With two bankable box-office stars at the helm and a limited 15-week run, he knew this wager would pay off.

“Think about it,” Davenport wrote. “[I]t’s not often that stars like this gather together to perform in a play like this, directed by a man like this. In fact — one could make a good bet that Denzel and Jake might never be on stage performing Shakespeare again.”

Fine and dandy. But if the play’s the thing to catch the conscience of a king, what truth does Othello catch during Project 2025’s relentless, premeditated, and conscience-free attack on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)?

Turns out, that truth is an old one

with a white supremacist thru-line that goes all the way back to Shakespeare’s time — threading its way from the American Civil War to Southern opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, to the New Southern Strategy of Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign, right up to the present moment and Project 2025’s ham-handed effort to undercut the 14th and 15th Amendments and wipe out the past 61 years of racial progress.

What we see onstage in this year’s Othello is a petty, vengeful bigot going out of his way to take down an accomplished high-ranking African American. This play is a 400-year-old mirror in which the past is reflected in recent current events.

In February of this year, for instance, while Othello was still in rehearsals, the recently appointed Secretary of Defense, a woefully unqualified man with white skin, fired General CQ Brown, Jr., the highly accomplished Joint Chiefs of Staff, who is African American. The reason given for Brown’s take down was his support of diversity and equity in the Armed Forces, but also because the Secretary said he didn’t know if Brown got the job because of merit or the color of his skin.

Ironically, within just a few weeks, this same Secretary of Defense, whose primary qualification seems to be his whiteness, has become the center of an epic military security leak that raises renewed doubts about his own merit.

General Brown’s dismissal is an egregious example of the current administration’s policy to remove diversity from government as well as other public and private organizations. But firing a man for supporting diversity is a clumsy cover-up for the real reason— the one that defines white supremacists more than any other.

“I hate the Moor,” Jake Gyllenhaal’s Iago says in a key soliloquy. He’s angry at being passed over for a promotion, but he’s got a big dose of racism going on beneath the surface. And one other thing — sexual jealousy. Iago sets out to destroy the Moor because he falsely believes Othello has had sex with his wife.

Iago’s lesson: smear campaigns work

Republicans have been complaining about DEI for years, calling it unfair and blaming it for ineptitude and inefficiency. Their constant barrage of negative branding eventually had an impact on public opinion.

In 2023, a Pew Research poll found a majority of Americans (56%) thought diversity, equity, and inclusion were good things. By 2025, after right-wing marketing reduced the meaning of those actual words to the acronym DEI, one poll shows 44% opposed with only 40% in favor. While a different poll puts those in favor at 51% with 44% opposed. Most of those opposed to diversity just happen to be Republican.

We have seen this before

During Reconstruction, similar negative branding falsely accused African American Congressmen of being lazy, ignorant, and corrupt. Today’s Republicans were called Democrats back then, but their intent was rooted in the same white supremacist goals as today. Their purpose? Stop Black Americans from fully participating in democracy. And if it’s possible to take down LGBTQ+ and the disabled with the same acronym, go for it.

Like any writer with his ear to the ground, Shakespeare knew that many of his countrymen were racist. His Othello reflects the widely held and openly shared prejudices of his day. Europeans during the Renaissance were concerned about some of the same issues white supremacists complain about today. Several 16th-century texts on racism and xenophobia document this.

Take the great replacement theory, for example—it’s not new. Many Renaissance Europeans also worried about it. In 1596 Queen Elizabeth issued licences to deport Africans due to “economic pressures” and because “most of them are infidels, having no understanding of Christ or his Gospel.”

But she was also alarmed by rumors that so-called blackamoors were having intercourse with witches and could also turn themselves into black cats and shaggy dogs. (As far as we know, she did not accuse them of eating the dogs or eating the cats.)

But wait…it gets worse

In 1578 when Shakespeare was 14, George Best published A True Discourse of Late Voyages of Discovery, which cautioned against expanded trade, claiming it could lead to miscegenation.

In Best’s view, intermarriage posed a terrible threat because mixed-race children jeopardized white homogeneity and superiority. Relying on the Bible, he claimed black skin was an infection, given to a son of Noah for his disobedience — an infection passed on in perpetuity to all his descendants.

According to Best, when a Black man married a white woman, the “infection” of the father’s blackness consumed the mother’s “fairness” and “good complexion,” turning the offspring black. He and other Europeans writing during the same period routinely described people with dark skin as subhuman with four eyes, “mouthed as a Crane, the other part of the head like a man.”

A lot of this language shows up in Othello

as the play takes aim at the prevailing European fear of miscegenation. Before the Moor ever appears onstage, we hear about him from three Venetians who describe him in a series of racist slurs, referring to his “thick-lips,” calling him “the devil,” and “a Barbary horse.” Iago even tells Desdemona’s father that an “old black ram is tupping your white ewe.”

Quite naturally, the girl’s father worries that his daughter has been bewitched. So Othello is summoned to the senator’s house in the middle of the night to explain. A task few actors have performed with as much dignity, eloquence, and grace as the great James Earl Jones.

It is during this speech that the audience sees Othello as an individual — not a racial abstraction. He is polite, honest, humble, patient, brave, heroic, and worldly wise. Watching him fall to Iago’s manipulation and his own jealousy is heartbreaking and tragic.

What the mirror shows

It’s too bad those who might benefit from seeing this play will not be able to. Either because they live too far from New York, can’t afford the expensive tickets, or just don’t have much interest in Shakespeare. Some of those folks will be told by their persuaders and influencers that Othello is for elites. And they will probably believe it.

For that reason, they will not see what this play reveals about men who think and act as Iago does. They won’t be able to put themselves in the place of innocent Desdemona when her husband asks, “Have you said your prayers tonight?” before he murders her.

Nor will they be able to witness for themselves that the hateful racist language in this play comes mainly from a despicable man. They won’t have an opportunity to hold the play’s mirror up to themselves and ask, Am I like this at all? Do I have any of this crap in me? If so, do I want it to remain there, festering forever?

Unfortunately, we live in such a confused time, many folks whose votes unleashed Project 2025 don’t believe they’re racist. After all they don’t use racial slurs. Some of them claim not to see color at all. As if the policies they support have nothing to do with it.

That is why, in times such as these, it is good to have a raw, two-fisted play like Othello. If it takes two Hollywood stars appearing in a Broadway revival to draw attention to this story about the evil that men do — then so be it. Maybe some who hear about the event will become curious enough to find a decent version online or in the library. Maybe then they will see that they have been manipulated into believing what is not true — just like Othello was.

©2025 Andrew Jazprose Hill | All rights reserved.

Thanks for reading/listening. Please hit the like, share, and/or comment buttons to help others find my work.

The evil that men do oft lives after them - I never thought to live again through such appalling attitudes and political actions. I had such hope for better angels in our government but I grossly misjudged my fellow countrymen. I fear that the current surge of white supremacy will crush all hard won progress of the civil rights movement toward equality and tolerance of difference of all types. How tragic that the prejudices that existed in the 1500s still have such power to disturb and disrupt. Those who want to rewrite history are too blind to see the damage they do.

Fascinating! Another stellar essay weaving together art, history, and currents events.