Leslie Van Houten's Hard-Fought Victory Over Evil

Why her quest for expiation after Charles Manson and the Tate-LaBianca murders recalls Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Mr. Rochester of 'Jane Eyre'

Click below for audio

Someday, I would like to ask Leslie Van Houten if she’s ever read “The White Album,” Joan Didion’s famous essay about the Tate-LaBianca murders.

That essay (and the book which bears the same title) begins with what is probably Didion’s best known sentence: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

What stories has Van Houten told herself regarding her role in the merciless killing of a complete stranger, 39-year-old Rosemary LaBianca in 1969? And how did those self-told stories change during Van Houten’s 53 years in prison?

Regardless of its permutations, her story must always include this inescapable fact: I did that. I held Mrs. LaBianca down while my companions stabbed her. Then I took the knife and stabbed her another 14-to-16 times.

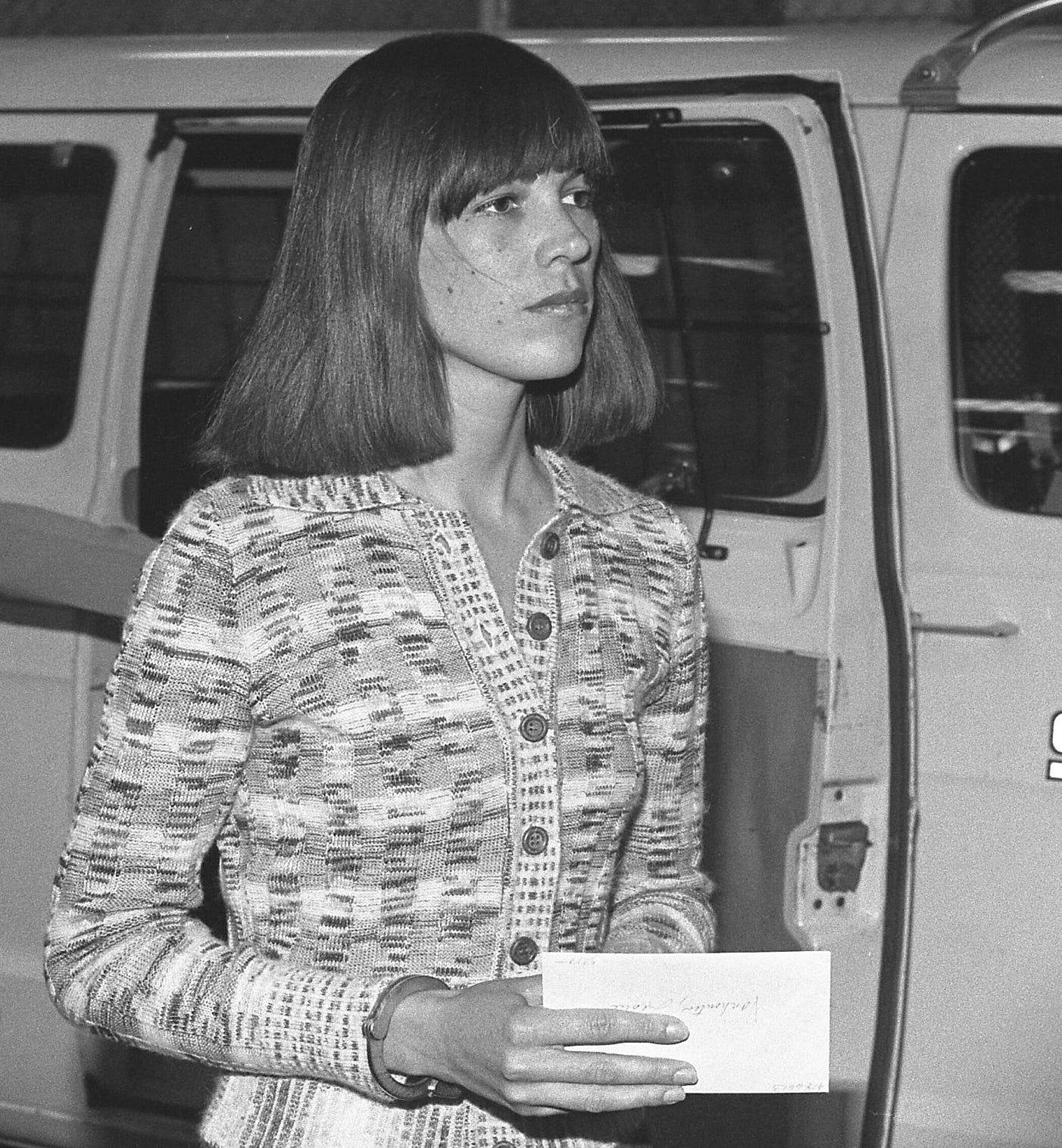

Leslie Van Houten was 19 years old

on the night of August 10th, when those nightmarish events took place. But when she was released from prison on July 11th at the age of 73, she looked nothing like the mouthy teenager who participated in that shocking crime.

She also bore no physical resemblance to Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh or Edward Rochester of Jane Eyre. But the three may very well be connected by a thorny link, which should not be dismissed.

The slaying of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca

was the second round of killings by members of the Charles Manson family during that terrible weekend. On the previous night, five Manson followers had brutally slain six others, including actress Sharon Tate who was eight-and-a-half months pregnant, and four of her friends.

Leslie Van Houten did not participate in the first night’s crime. But she did break into the LaBianca home the following night, where she took part in the attack that took both their lives. After killing her husband in the living room, Manson follower Tex Watson stabbed Mrs. LaBianca in the neck with a bayonet. Additional stab wounds were inflicted by a third gang member Patricia Krenwinkel. There was a lot of blood.

When Tex finished

he told Van Houten that she needed to do something too because Charles Manson wanted everyone to get their hands dirty. She then took the knife and stabbed Rosemary LaBianca multiple times in the back and buttocks.

Holding someone down so that someone else can stab them makes you a party to the crime. But that’s not quite the same as inflicting the death blow yourself. It is possible that Mrs. LaBianca was already dead by the time Van Houten stabbed her. And indeed, forensic evidence confirmed that many of the victim’s 41 stab wounds were administered after death.

In any case, Van Houten was tried three times before she was finally found guilty and sentenced to death. Her attorney died during the first trial, which led to a mistrial. Her second trial ended in a hung jury. She was finally convicted of murder in the third trial.

The only reason

she was able to walk out of prison half-a-century later is that the state of California outlawed the death penalty before she could be executed.

During her three trials, Van Houten refused to allow her attorneys to claim that she’d been acting under the influence of Charles Manson. But twenty-five years later, in an interview with Diane Sawyer, she changed her tune. This was a very different Leslie Van Houten than the mouthy 19-year-old who invaded the LaBianca home in 1969.

Now she was more than willing to point the finger at Manson.

This older Van Houten looked like a thoughtful upstanding member of society. It was clear from her clothes, comportment, and everything else about her TV appearance that she had changed. She’d also been able to draw on her upbringing in the middle-class suburb of Alta Dena. You can watch Diane Sawyer interview several members of the Manson gang, including Manson himself, in the clip below. [Van Houten’s part begins at 9:41 into the episode.]

The White Album

In describing the time leading up to the Tate/LaBianca murders, Joan Didion said that “a demented and vortical tension had been building in the community” for some time.

There were rumors. There were stories. Everything was unmentionable, but nothing was unimaginable. This mystical flirtation with the idea of “sin”—this sense that it was possible to go too far, and that many people were doing it—was very much with us in Los Angeles in 1968 and 1969.

Didion also wrote that she remembered the misinformation following the first night’s murders very clearly. There was talk of black masses, incorrect reports placing the number of victims at 20, the potential role of drugs. But she also remembered one thing more: No one was surprised.

The end of the innocence

Two years after Tate/LaBianca, Don McClean released a song about “the day the music died.” On the surface, this was a reference to the death of Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, and Richie Valens in a 1959 plane crash. But the lyrics of “Bye, Bye, Miss American Pie” put into music something many had been feeling for some time. The Tate/LaBianca murders struck the death knell for the innocent dreams of the Summer of Love.

When those unimaginable murders occurred, I was a year older than Leslie Van Houten and working at a group home for orphans in New York. An older Welsh couple in their mid-50s served as surrogate parents to five Black and Latino teenage boys during the week. Thanks to a college friend who recommended me for the job, I stepped in to relieve them on weekends.

Race war

What disturbed me about those gruesome murders as much as the crime itself was the intent behind them. Charles Manson wanted to start a race war. At both the Tate and LaBianca homes, his followers used the victims’ blood to smear the word PIGS on the walls, a term often used by the Black Panthers.

Manson hoped the outrageous nature of the slayings would incite a racial conflagration, after which he and his followers would come out of hiding and take over from Blacks who would defeat the whites but prove incapable of running the world by themselves.

This racist apocalyptic vision is sometimes overshadowed by the horrific nature of the actual crimes. But I could not ignore it as news of this Helter Skelter scenario came out. Not when I had white friends at college who felt the same as I did about creating a better more tolerant world.

And certainly not while I worked weekends as house counselor to five parentless Black and Latino kids, who were hoping to rise from socioeconomic disadvantage and become thriving members of society. One of the boys was really good with a needle and thread. He wanted to be a tailor when he grew up.

Did Leslie Van Houten deserve parole?

Based on coverage of her release, many people think not. Some still feel she should have been executed. An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a life for a life. The crimes were too heinous to be forgiven. The victims’ loved ones were marred forever by the murders. They deserve justice.

We are all still affected in some way by the aftershocks. Numerous films and true crime TV shows now focus on the underbelly of suburban life. As recently as 2019, Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood retold part of the Tate/LaBianca story as a flame-throwing revenge tale.

It is easy to see why so many feel like that. It’s as if the reaction of our reptilian brain were response enough.

But this view eliminates the possibility of expiation

I’m not talking about the Christian concept of expiation, which refers to the Crucifixion’s role in securing the release of humankind from sin. I’m referring to expiation in the broader sense. The kind that gives each of us a degree of agency in our redemption.

Take Mr. Rochester, for instance

Disappointed in love, the anti-hero of Jane Eyre becomes a philanderer, travels to a Caribbean island where he marries a mixed-race woman for her fortune, drives her crazy, then takes her back to England and locks her in the attic. He’s not a murderer. But he’s not a good man, either.

To make up for his crimes, Rochester adopts an orphan on the “principle of expiating numerous sins, great or small, by one good work.”

In the story Mr. Rochester tells himself, he is a victim of circumstance and betrayal. He must tell himself this story in order to go on living, even as he acknowledges his wrongdoing. But he also hopes to square himself with himself through this one good act of expiation.

Brett Kavanaugh

Like most Americans, I was riveted to Justice Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings back in 2018. I don’t think we’ll ever really know the truth of the sexual assault allegations made against him.

If he raped and harassed women in college and law school, as he was accused of doing, he should not have been elevated to the High Court. But if the allegations are true, there’s a case to be made that he later tried to atone for that behavior through numerous acts of expiation.

When he was a federal judge, 25 of his 48 law clerks were women. He is the only Supreme Court Justice whose clerking staff is comprised entirely of women. He coached his daughter’s basketball team for years, and was never accused of abusing any woman or girl he has worked with since those beer-drinking school years.

As the nation became divided over his appointment, it worried me that these later “good acts” seemed to count for nothing in light of the bad ones he’d been accused of. Not knowing the truth, I wonder what story Brett Kavanaugh tells himself.

Without expiation, there is no hope. And no forgiveness.

Imagine being condemned forever by the things you did at 19. The brain doesn’t even fully develop and mature until the mid- to late-20s.

The story Leslie Van Houten tells herself must always include the murder of Rosemary LaBianca, but she has a right to tell herself another story now too.

During her five decades in prison, Van Houten earned a masters degree in the humanities, participated in a range of mental health and self-help programs, wrote several short stories, edited the prison newspaper, and also tutored other inmates.

What were these good acts if not a form of expiation? Had she been put to death, she would not have had the chance to repent, rehabilitate, and atone for the wrong committed by her 19-year-old self.

To eliminate expiation is to wipe out the opportunity for atonement. Spell that word out and you get “At-One-Ment.” Which is what we all want. To be in harmony with nature, the divine, and our fellow man.

Leslie Van Houten’s release from prison is the story of her victory over evil. The evil that was Charles Manson’s hypnotic power over young girls. And the evil within herself. She has survived that struggle and is entitled to tell herself another story now. The story of a woman who can finally say, Free at last!

©2023 Andrew Jazprose Hill

Thanks for reading/listening. Please hit the LIKE, SHARE, or COMMENT buttons to help others find my stories.

In my Catholic grade school, the nuns taught us that a Catholic baptism created an indelible mark on our souls, presumably so we could be held to account at the last judgment. I always thought this was a curious idea, rather like branding a cow, but I later came to understand that this was just an extension of the idea that character is fixed at birth, and only divine intervention can move it. Thus, we always tend to go with the worst when evaluating someone's worth. Someone we thought was a good person does something bad, and we immediately think that their "true" nature has been revealed. I would be curious to know if this is a culture-specific idea, or if it's baked into our genes, the only truly indelible mark we have.

Whoops… wasn’t supposed to post yet !

In addition …it’s challenging to gracefully consider the perpetrators of these heinous crimes in light of those loved ones who remained - impacted/ haunted - for their lifetimes by these tragic deaths.

LVH has certainly created a life in prison that by certain standards is model behavior. Still , it’s hard not to judge. Certainly that parole board must have struggled or at least had reservations about their recommendation.

I love your comparisons to Justice Kavanaugh and Mr. Rochester. So well done, Andrew.