Part 1 Chapter 5

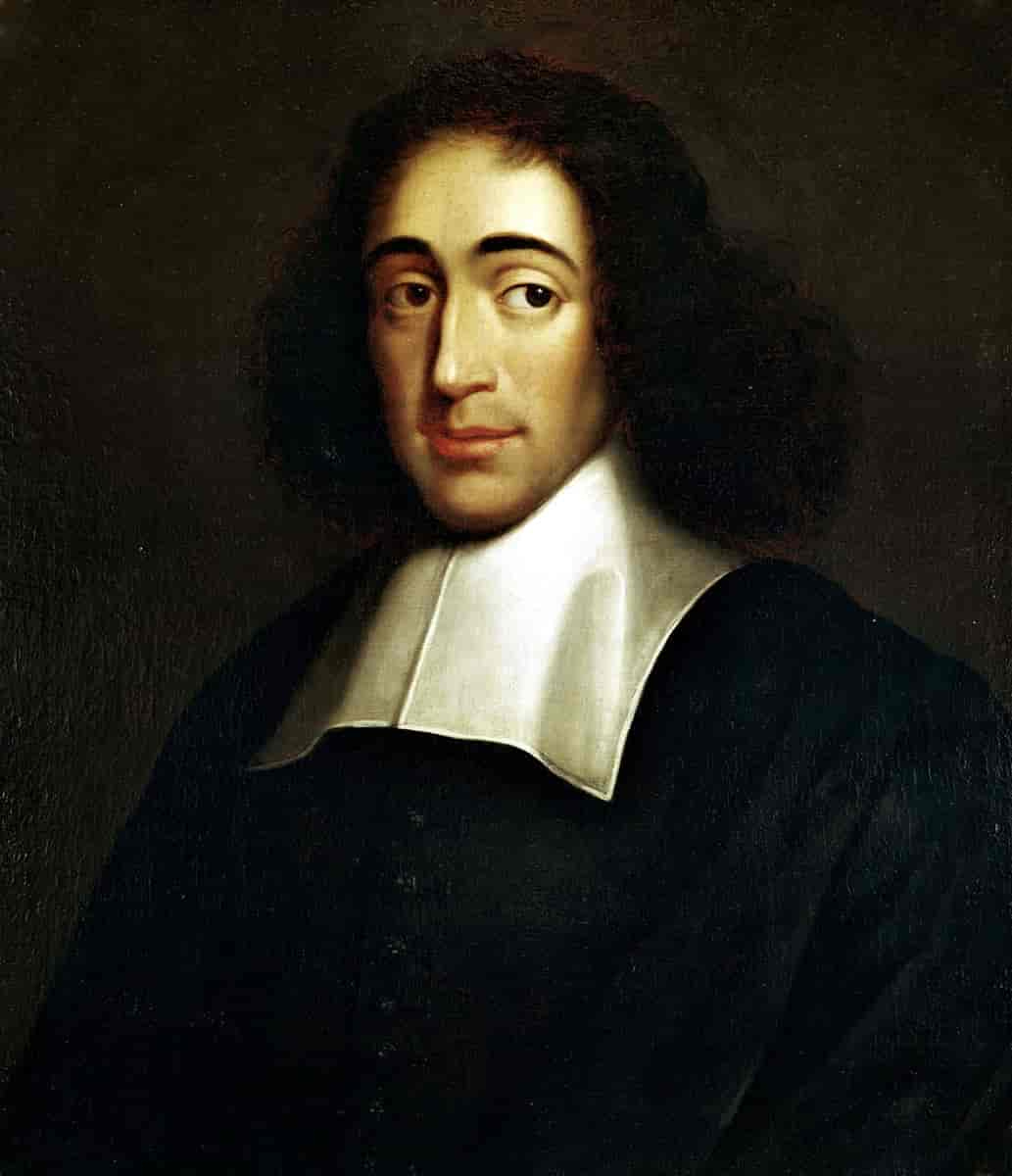

Spinoza

Now, nearly six months later, very little seemed to have changed when I boarded a train for Southampton, the first leg of my journey to America.

“You needn’t come with me,” I told my parents, who hadn’t listened.

“Why don’t you humor us, Rita dear? After all, it’s not as if we’re dropping you off at school. You’ll be gone for several months, maybe longer.”

My father’s voice had a slightly ironic, theatrical quality that must have been quite useful in the courtroom. It was the one thing he seemed to have in common with Uncle J. And perhaps that explained how my father, whose devotion to Spinoza, hard facts, and the rule of law, could maintain a lasting friendship with a man whose life was wedded to the make-believe.

His love of Spinoza had begun at university, where he found something of himself in the philosopher’s distinction between “adequate” and “inadequate” ideas. He fell in love with Spinoza’s belief in the indomitable primacy of reason and had taken up the principle like a religious vocation. Reason became the engine of his success, the sharp edge of his incisive arguments in court.

Unfortunately, he’d been unable to set aside Spinoza in his personal dealings. I’ve long felt that beneath his charming, statesmanlike demeanor, he looked down on anyone too strongly influenced by “inadequate ideas,” which Spinoza identified as emotion or intuition. In other words, inadequate people—like my mother and me. He never came right out and said this, but it seemed to hover always in the background, masked by his keen intelligence and personal magnetism.

And yet, there had never been one day in my life that I did not worship him.

“But it’s you two I’m worried about,” I told them as we queued up to board the train.

My father still wore his Hamburg like a statesman and kept his graying mustache as trimmed as when I was a child. But lately, his powerful voice, which had always reminded me of the gong at the start of a Rank film, had become phlegmy. It was beginning to sound like someone singing through a papered comb.

My mother, to whom I owe my rawboned physique and a fondness for language, now looked less like the leggy tennis player of her flapper-girl photographs and more like a fallen soufflé.

She wore a voluminous tweed suit and lavender blouse with a single strand of pearls draped elegantly round her neck. All her girlishness gone, she was now what’s known as a handsome woman. Self-sufficient and proud. But I worried about her more than my father. And I suppose that’s because I too thought her inadequate in some way. Though keen to put a good face on their marriage, as perhaps all couples do, something had been amiss in theirs for a long time.

End of Part 1, Chapter 5

@2021 Andrew Jazprose Hill

Thanks for reading/listening