In the spring of '27, something bright and alien flashed across the sky…and for a moment, people set down their glasses in country clubs and speakeasies and thought of their old best dreams.—F. Scott Fitzgerald

1

On the morning of the big announcement, Langston found the hairless face of his 9-year-old self staring back at him in the bathroom mirror. He shook his head, blinked, then looked again. But the vision was still there.

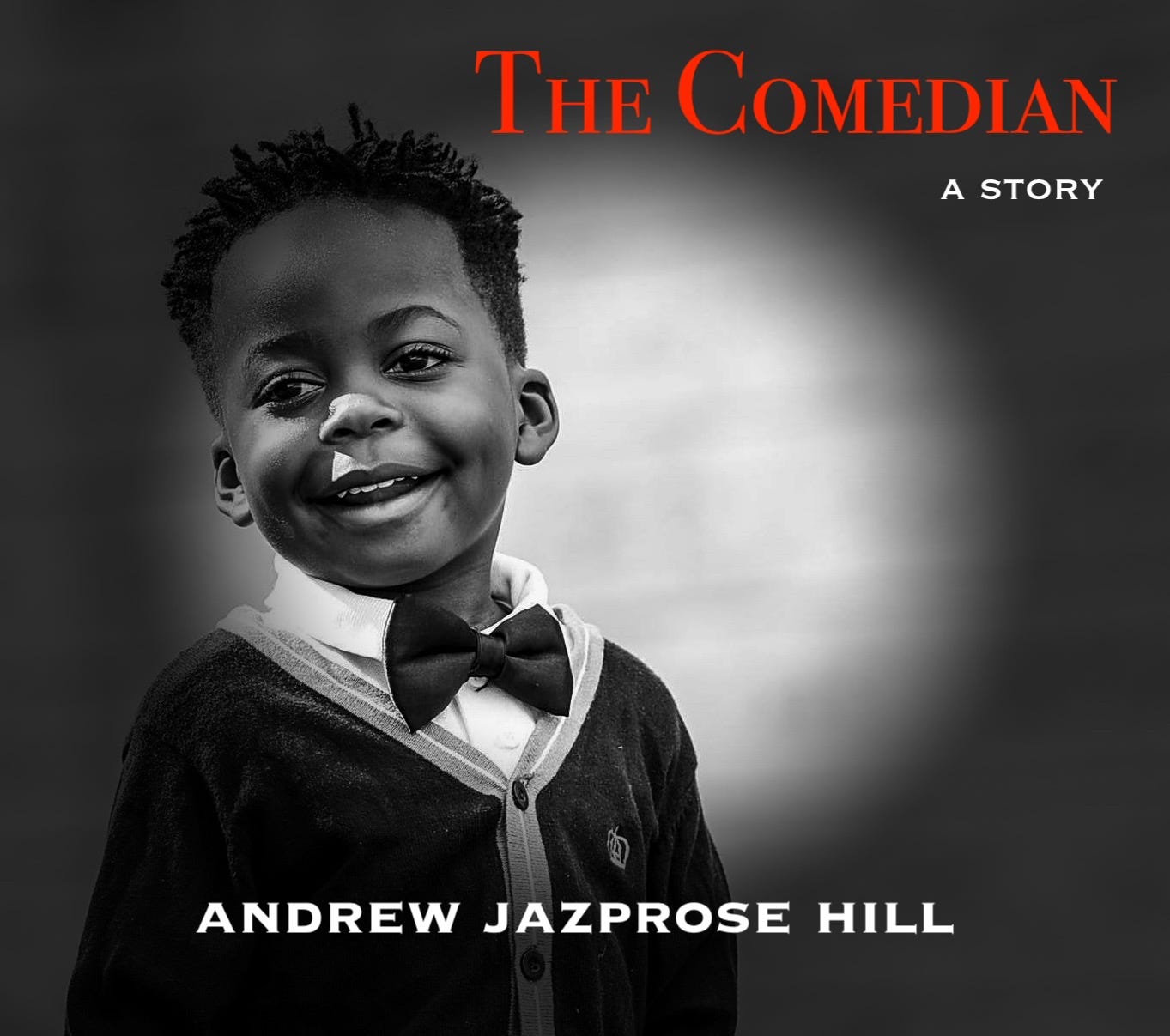

His boyhood face wore the same Coke bottle eyeglasses, which had led inevitably to the nickname that followed him all through school. Cokie.

His kid-self had bushy, not-quite-nappy hair that stood out around his head like tumbleweed. One of his front teeth had a chipped corner from when he tried walking backwards down a flight of concrete steps to impress Fanniette Thomas, a saffron-skinned fourth-grader who hadn’t even noticed.

Yep. It was Young Langston alright. This was the image he’d been unwilling to conjure a few days ago during his monthly visit with Dr. Peep Toe.

“It’s called regression therapy,” she’d said. “Sometimes it helps to understand how the inner child feels about who we’ve become.”

Langston did not want to know how his inner child felt. What was the point of growing up if the past still had a hold on you? His kid-self was gone. The thick glasses replaced with contacts. His tumbleweed hair shaved down to marble-smooth baldness in keeping with the times.

Grownup Langston had a beautiful wife and two fine sons who’d made it all the way to college. No drugs. No jail. No baby mamas.

Pictures on the walls of his suburban home revealed a smiling well-adjusted family—decidedly middle-class—at picnics, basketball games, graduations, bowling tournaments, and on the sunny deck of a gigantic Caribbean cruise ship.

Langston had become everything a successful American Black man was supposed to be.

So why did he feel that something was not quite right—off? And how could this so-called inner child scratch that itch?

Instead of responding to the psychologist’s questions, he focused on her grammar. Was it correct to say who we’ve become? Shouldn’t she have said whom we’ve become? He tried diagramming the sentence in his mind, an exercise that kept him occupied for the rest of the hour. As a result, the entire $200 session, like others before it, had been a waste of time. On every level except one.

Dr. Peep Toe was easy to look at.

She had shapely waxed legs and a symmetrical face. She wore round eyeglasses over blue eyes that seemed permanently set at F/1.4. Wide open. Like the Nikon lens he’d recently bought for a tidy sum on the Internet. Sometimes he felt he could tell her anything. But just as he reached the point of surrender, he’d detect a clinical distance behind that come-hither mask. This was the kind of woman who would kiss you with her eyes open.

Her real name was Jennifer Dinsmore, PhD. But Langston liked thinking of her as Dr. Peep Toe. Everything about her was buttoned up and strapped down. She wore modest knee-length skirts (no thigh, thank you) and silk pastel blouses (no cleavage, either) under tailored two-button blazers, the uniform favored by HR professionals and female candidates for public office.

She came across as neutral, nonthreatening, asexual. Like a secular nun. Except for her shoes. Jennifer Dinsmore, Ph.D., favored heels with an opening at the tip through which two apple-red toenails poked out like excited ganglia.

Langston hadn’t wanted to enter therapy. It was Jinx who pushed him to do it. Jinx, his mentor and friend. Jinx who was right about everything.

“We all need a tune-up once in a while,” Jinx said. “Besides, the company’s paying. You might as well do it.”

So far, Dr. Peep Toe hadn’t helped at all. Langston still had trouble sleeping. Still worried that his wife might someday leave him. Still felt stuck on a bullet-train speeding at 200 miles per hour toward the wrong destination.

Not that he didn’t enjoy talking with the psychologist. Sometimes, like last night, she appeared in his dreams wearing only her undergarments. Now here was cleavage, here was thigh, here were those sexy open-toe shoes. During the nocturnal visit, she looked at him inquiringly, her question from their last session still on the table.

This dream had opened a portal he tried to keep closed during their sessions. The face of his kid-self in the mirror took him back to his third-grade class at St. Michael’s. He saw himself in a white shirt, blue necktie, and a navy blazer with the school’s monogram embroidered in gold thread over the breast pocket. He’d only been an average student, remarkable for nothing except his tumbleweed hair and thick Coke-bottle eyeglasses. Until one particular day in third grade.

2

“Why did God make you?”

From the mouth of Sr. Margaret, the question felt like the cross-examination of a hostile witness. She’d been scribbling words from the Baltimore Catechism on the chalkboard, an oversized rosary dangling from her waist, black veil trailing behind her like batwings. Then, she spun around and pointed a wrinkled white finger right at Langston as if divine revelation had singled him out as the pupil least likely to know the answer.

Langston had no idea why God made him. But he wasn’t about to let this pale white nun make a fool of him in front of the entire class.

With the innocence of a cherub, he boomeranged the question right back to her.

“Because He wanted someone to go bowling with?”

The thirty-odd witnesses to this exchange needed little excuse to disengage from the rigid conformity of their daily lot. They let go with watery-eyed abandon, hooting, clapping, slapping their palms on the desks—a commotion that halted abruptly when hoar-faced Mother Agnes, her eyes fiery over the top of wire-rimmed glasses, flung open the classroom door.

“What is the meaning of this?”

“Mr. Ragsdale thinks God created him because He needs a bowling companion,” seethed Sr. Margaret, whose wimpled face had turned red.

“I’ve had quite enough of your nonsense, Mr. Ragsdale,” the principal said. “You think you’re a comedian? We’ll see about that. Come to my office this instant. The rest of you, get back to your lessons!”

Langston stole a look over his shoulder as he followed the snowman-shaped figure of Mother Agnes from the classroom. A wave of satisfaction swept over him. His classmates were back in their invisible strait-jackets now. But for a moment, he had released them. Brought them joy. He, the unexceptional Langston Ragsdale— Cokie—had done this.

From that day forward, he had only one wish. Maybe Mother Agnes had put a name to something he had always known. Maybe it had nothing to do with her but sprang from his own impromptu stroke of genius. Whatever the reason, whatever the cause, something crystalized within him in his third-grade class that day as he bowled a perfect strike against Sr. Margaret. That’s when he knew for sure that he did want to be a comedian. To spend the rest of his life making people laugh.

3

Shaving his increasingly gray stubble while the smooth face of Young Langston gazed back at him, he remembered the dark side of those growing-up years from which the comedic urge had sprung. The chaotic eruptions that came without notice as his parents’ after-midnight arguments woke the household.

Arguments over things he did not understand. Lipstick of a color his mother did not wear. The dented Oldsmobile languishing flat-tired in the driveway. His father’s expensive Panama hat. The whiskered gray-haired Watkins man, who went door-to-door selling medicinal products from a leather case.

Why any of these things should lead to the breaking of glass and the overturning of chairs was a mystery. As were the shouts, tears, and whispers that eventually seeped into the walls, biding their time till summoned again like ghosts.

And yet despite these unpredictable outbreaks, Sunday nights had a quality of light about them, which began with the beam of a black-and-white TV set, then grew like a campfire into an enfolding luminescence.

The TV was a floor-model RCA encased in mahogany. Sunday night was the only time the family sat down together after the usual dinner his mother cooked to mark the specialness of the Lord’s Day: roasted hen, collards, white rice, and sweet potato soufflé. For Langston, those evenings surpassed even the Catholic Mass for which they denied themselves breakfast on those same Sundays, fasting in order to receive the sacred Host.

Except for the bread and wine of Holy Communion, God was invisible. But you could see George Burns, Jack Benny, and Sid Caesar on television. Flip Wilson and the as-yet untainted Bill Cosby, too.

“Take my wife, please,” said one comic. “I get no respect,” said another. And even though Langston had no idea why these jokes were funny, he laughed because his parents sniggered with wry nervousness, their troubles seemingly behind them.

What he admired most was how the comedians brought his family together. How the high cheekbones of his father’s clan seemed to merge more closely with the deep-set eyes and long noses of his mother’s side. How ineffably linked they seemed as they teetered on the edge of a punchline. Trying to catch the joke.

Langston rarely thought about those days now. But with his nine-year-old self staring back at him in the mirror that morning, he understood what he must have known instinctively as a child. Like the lotions, salves, and ointments brought to their door by the gray-whiskered Watkins man, laughter soothed the inflammation that flared up all too often in his childhood home. It was the balm that relieved the pressure of his parents’ daily scramble to make ends meet.

Distracted by these memories, he nicked his chin. Blood drooled from his face, tracing a thin red line into the white hollow of the sink. He tore off a square of tissue and stuck it to his face to stanch the flow.

4

“Well, today’s the day,” Denise said, lightly kissing his cheek at the front door to keep from smearing her lipstick. Then tapping his chin near the tissue, she said: “Guess you’re a little nervous, huh?”

“Yep, today’s the day,” he repeated, ignoring her allusion to the razor cut.

“I’m so proud of you, Langston. You’ve worked a long time for this. I wish the boys could be here.”

The “boys,” named for positive Black role models just as their father had been, were grown men now with lives of their own. Frederick was in his final year at Georgetown. Nathaniel was on a fellowship in London and sounded increasingly British each time he phoned home.

“They gon throw us out of the NAACP if that boy don’t snap out of it,” Denise said after one of Nat’s trans-Atlantic phone calls. This was as close to a Black accent as Denise could manage these days. Like Langston, she had lost the ability to code-switch long ago.

“We should celebrate,” Langston said. “Why don’t you put on your high-heel sneakers so we can trip the light fantastic like in the old days?”

Denise held him at arms-length, her eyebrow arched.

“You want to go dancing on Zoom?” She held up a surgical face mask, then pressed it into his palm like a folded dollar bill.

“I have plenty of these in the car,” he said, “and hundreds more at the office. Don’t know how I could let myself forget about the plague, even for a moment.”

“Don’t worry, Lanky. I’ll get Door Dash to deliver a five-star Zagat-rated meal, and we can have one of those nice wines we’ve been saving for a special occasion.”

She held out her cheek so he could kiss her.

“And Lanky?” She paused, weighing her words. “Nobody says ‘high-heel sneakers’ or ‘trip the light fantastic’ anymore. It’s dated.”

Dated.

“I’ll trip your light,” he said, feeling some of the old passion stirring again despite himself.

He didn’t mind that Lanky, her pet name for him, had replaced the Cokie he’d grown up with. What he minded was that this woman, whom he had loved all his life, had remained somehow unattainable after all these years. Though he possessed her physically, had watched her give birth to their sons, he’d never been able to shake the feeling that he was not quite good enough for her. That she would one day stab him in the back, if she hadn’t done so already.

“Has your wife ever given you a reason to doubt her?” Doctor Peep Toe had asked.

“No.”

“Does she stay out late, flirt, receive secretive phone calls?”

“No.”

“Do you do any of these things?”

“No.”

“Then why do you suppose you feel this way?”

“If I knew the answer to that I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you.”

End of Part 1

©2022 Andrew Jazprose Hill