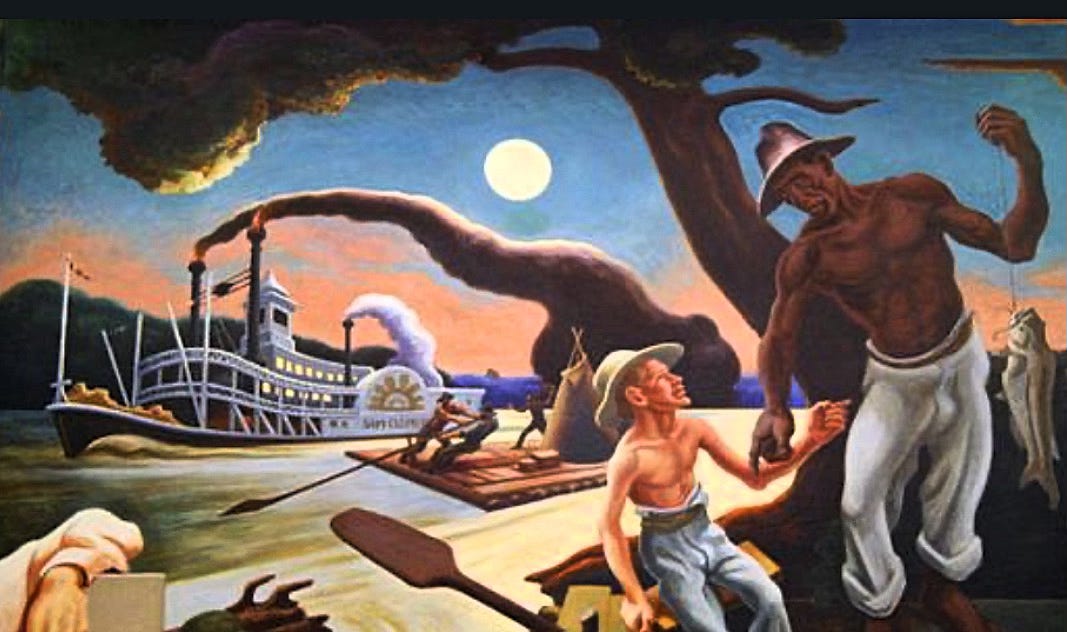

What the Huck?

Why should we care about the story of a Black man and a white boy on the Mississippi River told from the Black man's point of view?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Jazprose Diaries to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.