Why I Love My Fake Noguchi Coffee Table

This year, as part of its ongoing attack on People of Color, the White House rescinded Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. But it can never revoke this icon of personal transcendence.

Someday, maybe I’ll be flush enough to drop $2600 dollars on an authentic Noguchi Coffee Table. But for now, I’m fine with my cheap knock-off, which bears a striking resemblance to the real thing.

Sometimes the idea of a thing can be just as meaningful as the thing itself. And when it comes to the iconic Noguchi table—a masterpiece of midcentury modernism—the idea and the story behind it are everything.

This year, however, the story of that table is more important than ever. Which is why I want to repeat it before the month of May, traditionally observed as Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (AAPIH) comes to an end.

Since the early 1990s, after George H. W. Bush signed a bill to extend Asian-American Heritage Week to a full month, May has been officially designated as a time to recognize the heritage and achievements of the AAPIH community.

But in January of this year, as part of its anti-DEI crackdown on People of Color, the White House issued Executive Order 14148, which rescinded federal recognition of AAPIH month and dissolved the 1999 White House Initiative on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, which was re-established under the Biden administration.

It’s the same old stuff

American history is full of racially driven embarrassments like this. Like slavery and segregation. The Indian Removal Act. The Chinese Exclusion Act. And the internment of Japanese American citizens during World War II—80 thousand of whom were second-generation American-born Japanese (Nisei) and their children (third-generation Sansei).

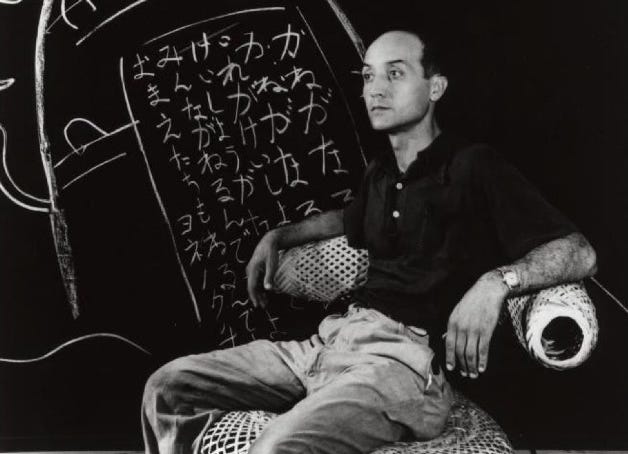

This is where the story of Isamu Noguchi and his iconic table come into the picture. The mixed-race son of a Japanese poet and an American writer, Noguchi was already an accomplished and well-known artist living in New York when the war broke out.

Although exempt from relocation because he did not live on the West Coast, Noguchi hoped to use arts and crafts to improve the conditions of those who were forced to relocate. So in 1942, he traveled to Arizona, where he became the only person to enter an internment camp voluntarily.

When it became clear that the government had no intention of implementing any of his ideas or using his designs, Noguchi decided to leave but was prevented from doing so. Earlier that year, he had co-founded an artists’ group that tried to raise awareness about the injustices of relocation. He wrote to President Roosevelt and assembled a group of prominent artists to testify before Congress. But to no avail.

As a result of these activities, intelligence officials decided that Noguchi was a suspicious person. Even though he’d entered the internment camp of his own free will, he’d become a prisoner.

What does a coffee table have to do with all this?

In 1939, three years before his internment, Noguchi met with prominent British architect T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings, who asked him to submit designs for a three-legged coffee table. Hoping to gain a commission, Noguchi created several plastic models and sent them to the architect. But he never heard back, and since he was busy with other projects forgot about all it.

Until he opened a magazine during his confinement—and discovered that the table he had designed for Robsjohn-Giddings was being marketed and sold without his consent and without any compensation.

After several petitions and loads of red tape, Noguchi was finally released from the prison camp in November of 1942. That’s when he confronted the architect. Instead of offering him compensation or apologizing for using his design, Robsjohn-Gibbings basically told Noguchi to get lost, adding: “Anyone can make a three-legged table.”

This is where the good stuff happens

Noguchi could’ve gone home and cried in his cups about the injustices he’d experienced. He could have become a bitter hateful man. But instead of becoming despondent, he decided to do something else.

If it was true that anyone could design a three-legged table, he would create a unique design of his own—something no one else could claim as theirs. Channeling his anger and frustration, he got to work. And eventually he came up with a coffee table the likes of which had never been created before. A table that uses only three pieces—two curved wooden legs and a piece of glass.

Joined by a metal pin, the two legs form the three points of a triangle held in place by the weight of the glass. It’s a work of genius. Immensely popular with consumers, the Noguchi Coffee Table has been on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York and also at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City.

Why this is important

Write it off as conjecture if you must, but I believe Noguchi experienced a spiritual breakthrough, a moment of transcendence, while working on his new design.

Several years ago, I attended a two-day seminar on the necessity of beauty in our everyday lives, sponsored by the Jung Institute of San Francisco. One of the speakers was a music professor, who discussed the role of transcendence in the work of Ludwig van Beethoven after he became completely deaf.

Taking his seat at a Steinway, the professor played the composer’s Piano Sonata #29, also known as the “Hammerklavier” sonata. He paused during a particular musical phrase halfway through the piece to illustrate the exact point at which Beethoven experienced a moment of transcendence while composing the sonata.

That moment was so powerful, said the professor as he played the phrase several times, that Beethoven couldn’t express everything he wanted to say about it in a single sonata. So he used it again in two longer works—the Missa Solemnis and his famous Ninth Symphony.

Any artist who’s ever experienced this understands that it’s a gift. When asked how he managed to get such extraordinary performances from his internationally renowned chorale, Atlanta conductor Robert Shaw put it like this. “You practice and you practice and you practice—and on the day of the performance, hopefully the Holy Spirit will come down.”

Other examples

When Catholic cardinals met earlier this year to select a new pope, several of them later said the process involved a series of prayerful discussions until they felt inspired by the Holy Spirit.

Students of American history will recall the philosophical and intellectual movement of the 19th century known as transcendentalism, which included Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Margaret Fuller. Intuition was a key component of transcendentalism, which sought to combat the rising materialism of the time. And what is intuition but another way of describing transcendence and/or the Holy Spirit.

No doubt you’ve heard the saying: Prayer is man speaking to God. Intuition is God speaking to man.

That’s when something great happens. And that’s what I think Isamu Noguchi experienced while working on the design that became his iconic coffee table—whether you call it intuition, inspiration, transcendence, or the Holy Spirit.

But one has to be actively engaged in something in order for this to happen. As a novelist once said of African American poet Robert Hayden, his poetry sought 1“transcendence, which must not be an escape from the horror of history or from the loneliness of individual mortality, but an ascent that somehow transforms the horror and creates a blessed permanence.”

That idea is certainly present in the Noguchi Coffee Table. That’s why I don’t mind having a faithful reproduction for the time being. Every time I see it, I’m reminded that the artist endured one injustice after another but rose above it, reaching higher ground where the view was very different from what came before.

Noguchi created that table decades before Maya Angelou wrote her famous poem “And Still I Rise” in 1978. But the message I see in that table is the same message I hear in her poem. One artist was Japanese American and the other African American. Both were People of Color who understood the universality of the human condition. And who left us with potent reminders that we need not be defined by any force that seeks to deny that.

©2025 Andrew Jazprose Hill/All rights reserved.

Thanks for reading/listening. Please hit the like, share, and/or comment buttons to help others find my work.

Thanks to my friend poet Dennis Sullivan for making me aware of this important African American poet.

Your ability to connect seemingly unconnected pieces into a coherent and powerful statement makes your work a compelling read. This piece is no exception. And, I always learn something new! Bravo.

Such a beautiful table and the story behind it, and such a beautiful essay bringing all of that to light. I love the idea that he reached a moment of transcendence when creating his table. I believe it underlies all great works of art, something higher than ourselves moving through us, expressing itself through us. Thank you, Andrew. I always feel blessed when I read your essays.