Last night before the sky got dark, Jeff Snow passed me on the dock and did not speak as he went by. I saw him first, about 20 yards before we met, his face distinct in a tangle of tourists. I knew who it was, but I didn’t say anything either.

Ordinarily, Jeff would not stand out in a crowd—he’s an average-looking guy with brown hair. But he walks with a limp that distinguishes him when he might prefer to remain unnoticed.

Sometimes the limp is more pronounced than at others. You see him leaning on his cane, wrestling with some force between the dock and his wrist, his head and forearm trembling with effort. That’s when he gets this unusual look in his eye. Like he’s focused on something about 45 degrees due east of everydayness. It’s not a look that goes inward like the enlightened gaze of a guru. It’s the kind of look you see in a veteran’s hospital or a home for the aging. The look of someone who’s here but not here. On Jeff, it’s something you notice because his eyes, blue as bachelor’s buttons, seem too young to have such a look.

He doesn’t always look that way

Nor does he always struggle so intensely with the cane. But when he does, I leave him alone. I don’t pull him out of his thoughts for the sake of my mundane hello. That’s why I let him pass me on the dock last night without speaking. I watched as he looked right past me, and I let him go.

There was a space of about three seconds as we moved five, maybe ten feet apart. Then I heard him call my name.

“Hey,” he said, “I didn’t even realize it was you.”

Smiling, he stretched out his hand to shake mine, so I turned and went back a few paces to greet him.

Jeff is a friendly guy, and I like running into him even though we never have that much to say. We talk sailboats. About his beautiful flush-deck Cal 25 and my sloop-rigged Erickson, which sails, I tell him, a lot better than I do. That’s how we talk. You know how it is. With some people you have the same conversation every time you see them. You just use different words.

But last night, with Jeff, something extra happened

“I’ve got this new roller-furling system,” he said, “and it jammed while I was out there this afternoon.”

He described how the headsail was flapping in the wind and he couldn’t get the new furler to roll it back up like a window shade the way it’s supposed to. He had to tie the tiller so the boat would heave-to—go around in a circle instead of heading off into the rocks. Then he stepped forward to the bow, got down on his belly, and unjammed the mechanism.

This may seem a small thing to someone who has crossed the Pacific or lost a mast in a storm. But it was not small to Jeff. And it was not small to me. It has only been about two and a half years since I first learned to sail single-handed. I know how things can go wrong.

You get a line fouled in a propeller. The fuel filter clogs, the engine dies, and there’s no one out there but you to take care of it. No crew, no wife, no buddy. Just you alone to meet the challenge of the unexpected and get yourself back home. It’s always something that’s never happened before, a crisis that will create you and reveal you to yourself. Whenever I’ve come back from sailing solo, I’m alive with energy for hours.

That’s how Jeff was last night. He wasn’t bragging. I know. After all that time out there alone, he wanted to tell what he’d experienced. But to put it in perspective, he had to add one thing more.

“I was in a coma once,” he said, “and now I’m disabled. One day I was riding my bicycle, and I got hit by a car. I was 16. Now I’m 23. The coma lasted for a month and a week. And then one day I came out of it. I was in a wheelchair for a while, and the doctors said I would never walk again. I made it to crutches, and they said I would probably always have the crutches. But now all I use is a cane, and today, as you can see, I’m not even using that.”

Can you see what this means?

I felt him say between the lines. I was on death’s own threshold once, but today I was in the dance, man. Out there in a pocket of life between the wind and the current, having a blast.

I wanted to embrace him. Instead, I looked down at his legs, thin and uncertain in Bermuda shorts, and saw the scars that proved his past.

“It was seven years ago yesterday that I came out of the coma,” he told me. “This is the seventh anniversary of my coming back to life.”

There’s probably something significant about the number seven in all this. It may be simply that Jeff’s body remembers he once did something extraordinary at this time of year and commemorates it now by yet another extraordinary deed of a different kind. Or maybe there is a mystical, numerological side to it. Some occult, psychic thing I am not able or interested enough to pursue.

And yet, I was happy last night because some guy I hardly know, and almost did not speak to, had gone out alone in a sailboat. I said goodbye to Jeff on the docks and forgot all about the Olympics when I got home.

That was then; this is now

Years later, after I had left the island and had long since given up my sailboat, I reconnected with Jeff via Facebook. When I originally published the story of our encounter in the Seattle Weekly, I changed his name to protect his privacy. But a short time later, Reader’s Digest republished the piece as “Kevin’s Conquest.” Although his real name had not been used in the story, Reader’s Digest had a wide enough reach that it soon became clear on that remote island at the edge of the continent that the pseudonym applied to Jeff.

“You should have used my real name”

He said when I saw him after the Reader’s Digest piece appeared. “If you ever write about me again, please use my real name.”

This was an easy promise to keep, but I was not able to find a publisher for the book I eventually wrote that mentioned Jeff.

Maybe that’s a good thing because it turns out there was one other element to his story I would find out much, much later from one of his Facebook posts.

After his bicycle accident, Jeff had been unresponsive for some time. The doctors suggested it might be best to remove him from life support. But his father Robert Snow refused to let that happen. Robert always believed his son would regain consciousness. So he stood by, watching for any signs the busy medical staff might miss. His father’s faith paid off. Jeff came round again and was well enough to single-hand his own sailboat seven years later.

Every once in a while I see a post that says, Prayer changes things. And I wonder what kind of prayer—what kind of faith—it takes to bring a boy back from a coma. For that matter, what kind of love.

I once read a book that measured medical outcomes for people who were prayed for against outcomes for those who were not. The author found that people who were prayed for fared better statistically.

Magical Thinking?

And yet, I know of people who refer to this as “magical thinking” and refuse to take it seriously. One was a woman who tried every conceivable treatment to cure her handsome young husband of cancer, and he died anyway. She gets disgusted whenever she hears of folks hoping against hope for that last-minute reprieve. Praying for miracles that she believes will never come.

Another friend was still a teen when his much-loved eldest sister died of a long illness, even though he prayed with all his might for a cure. When she died, he turned to crime and became a juvenile delinquent until a good therapist helped him get in touch with his grief. He eventually became a psychologist himself and has spent the rest of his life helping others.

We want our stories to have happy endings

But they don’t always. We impose our narratives on the lives of others, hoping to find solace for ourselves. Proof that life has meaning. That if we blow on the dice just hard enough, they will roll in our favor. But quantum physics tells us life in an expanding universe is neither random nor predetermined but a series of infinite potentialities. If we move this way or that, say this prayer or another, can those things affect the outcome?

Jeff’s story did not end when he came out of the coma. There would be new stories for him, new struggles, new conflicts. People who don’t know what he’s been through see a middle-aged man struggling to keep his balance—and imagine that he is drunk. A few hurl insults. Some laugh. They do not realize or have forgotten that life can change in an instant. And there but for the grace of God…

To further public understanding and in lieu of wearing a sign that says he has Cerebellar Ataxia from his Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), Jeff has posted information online about the lasting effects of his injury. The symptoms of TBI include tremors or shakes, stumbling and difficulty walking, dizziness, short attention span, and difficulty finding words. Although the symptoms are remarkably similar to inebriation, it has to hurt when strangers accuse him of public drunkenness.

The tagline on Jeff’s Facebook page echoes what Atticus Finch told his daughter Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird. “Before you criticize me,” it says, “walk a mile in my shoes.”

Over the next few weeks as we watch the Winter Olympics in Beijing, it might be a good idea to recall that not every hero wins a medal. Not every hero is in the limelight. Some struggle alone. Counting victories and defeats we will never see.

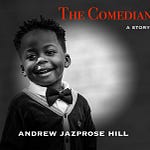

©2022 Andrew Jazprose Hill

Thanks for reading or listening to the Jazprose Diaries. Please hit the like, share, or comment buttons to contribute to the conversation. Have a wonderful day.

Share this post